Most other environmentally sensitive buildings rely on advanced machinery: hyper efficient air conditioners, motion-activated window shades, and so on.

HouseZero dispenses with contraptions that refrigerate the house in summer or blast heat in winter. Maintaining a comfortable indoor temperature depends on an ingredient that most architecture forcibly exclude: fresh air.

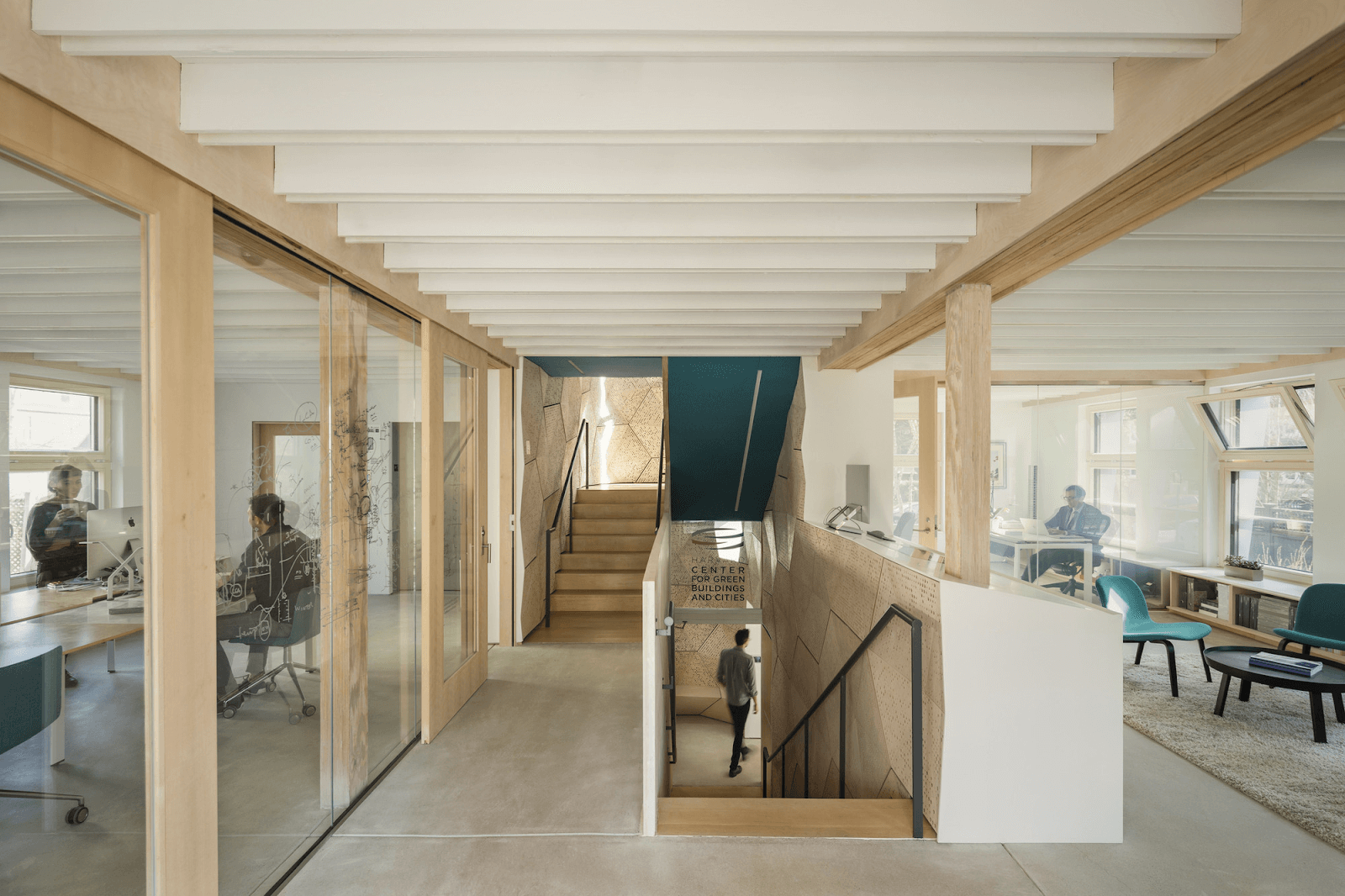

The center’s director, Ali Malkawi convinced Harvard to pay to take the place apart and rebuild it with off-the-shelf components, including a geothermal heat pump to take the edge off heat waves and polar vortices. Thicker-than-typical concrete floors absorb and radiate heat, and there’s an extra layer of insulation in the walls.

But the real innovation lies in the software, which continuously regulates windows and vents to keep air flowing through the building and achieve ever-finer gradations of comfort. Graduate students keep refining the algorithm, sifting through the 16 million data points that the house’s sensors collect each day and gauging how cloud cover, air temperature, and the foliage on the trees in the yard interact with the staff’s clothing, how closely their warm bodies cluster in each room, and how much carbon dioxide the houseplants vacuum up.

Everyone knows that warm air rises, but here, sensors in a chimney can study the nuances of real-time convection flows to see exactly what happens when a flue is nudged or a door swings open three rooms away. The house can respond immediately or over time: A computer calculates how much warmth the concrete floor slab has stored during daylight hours, how much will be released overnight, and how quickly to blow that heat away or trap it inside, depending on the next day’s forecast.

“Understanding building behavior is one goal to the research; the other is to figure out how can we command buildings,” Malkawi says. “The idea is to allow the building to use data, learn, and adjust.” – Malkawi