The Montreal Biosphere (French: La Biosphère de Montréal), often known as The Biosphere (French: La Biosphère), is a museum devoted to the environment. It is now housed in the old United States pavilion, which was constructed for Expo 67, and is situated inside the Parc Jean-Drapeau grounds on Saint Helen’s Island. The museum’s geodesic dome was designed by Buckminster Fuller. It is now housed in the old United States pavilion, which was constructed for Expo 67, and is situated inside the Parc Jean-Drapeau grounds on Saint Helen’s Island. Designed by Buckminster Fuller, the geodesic dome of the museum. (1)

The Montreal Biosphere is a well-known environmental museum in its current form. Air, water, biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable development are just a few of the subjects that visitors to the unusual dome are interested in learning about.

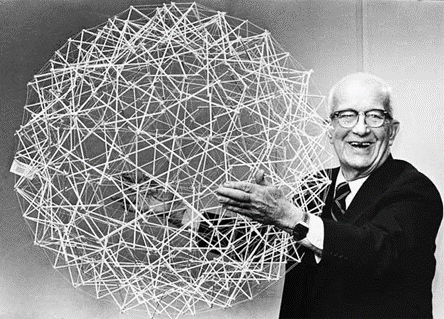

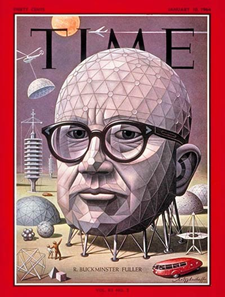

Buckminster Fuller: The visionary architect

Richard Buckminster Fuller was an American architect, systems theorist, author, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist who lived from July 12, 1895, until July 1, 1983. He published more than 30 books under the pen name R. Buckminster Fuller, going by that name in his writings. He is credited with creating or popularizing terms like “Spaceship Earth,” “Dymaxion” (as in “Dymaxion houses,” “Dymaxion cars,” and “Dymaxion maps”), “ephemeralization,” “synergy,” and “tensegrity.” (2)

The widely recognized geodesic dome was popularised by Fuller, who also created a number of innovations, mostly architectural ideas. Scientists eventually identified carbon molecules called fullerenes for their structural and mathematical similarity to geodesic spheres. From 1974 until 1983, he also held the position of Mensa International’s second world president.

The construction of the Montreal Biosphere

The dome, constructed with a steel skeleton frame and an acrylic covering, is a sphere that exhibits American cultural contributions such as spaceships from the Apollo missions and artwork from around the country. Around 5.6 million visitors to Expo 67 were in awe of the sphere’s enormous, jewel-like design. (2)

Geometrically, the dome is an icosahedron, a 20-sided shape formed by the interspersion of pentagons into a hexagonal grid. The fragmentation of this form’s faces, which are divided into a series of equilateral triangles with slight distortions that bow the individual planar sections into shells, obscures the form’s clarity, though.

Because of this, the dome’s overall structure is significantly more spherical than simple icosahedra. While the smaller, through sheer repetition, units create dazzling visual complexity, The entire lattice-like structure is made of three-inch steel tubes that have been welded at the joints and gently tapered toward the top to evenly distribute forces throughout the system. (3)

Key architectural features of the dome

At a diameter of seventy-six meters, the expansive sphere reaches an astounding sixty-two meters into the sky and thoroughly dominates the island on which it is located. Its volume is so large that it could easily accommodate a seven-story exhibition building housing all of the exhibit’s programmatic components. (3)

A complex system of shades was used to control its internal temperature. The architect made an effort with the sun-shading system to mimic the biological mechanisms that the human body uses to regulate its internal temperature. Fuller’s original design for the geodesic dome included “pores” to further resemble the sensitivity of human skin, but the shading system didn’t function properly and was eventually turned off.

The idea behind the dome

Architecture, in this model, was intended to exist in close contact with both mankind and nature, playing civilization’s most critical role in elevating the state of humanity and promoting its responsible stewardship of the environment. This melioristic viewpoint, which grew out of the ethical positivism of postwar modernism, represents perhaps the pinnacle of optimism’s rise in mid-twentieth-century thought and provided Fuller with a particular moral framework for his revolutionary designs. (4)

An iconic vision for further generations

Through holistic consideration, systemization, and mass-production, Fuller saw this project as an example of how architects could wield and deploy the instruments of innovation to create new species of hyper-efficient machines for the good of mankind.

Pure geometries like those found in the Biosphere are beautiful as an added bonus, the deliberate but secondary achievement of a functionalist and moral endeavor. (4)

REFERENCES:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montreal_Biosphere

- https://espacepourlavie.ca/en/biosphere

- https://www.archdaily.com/572135/ad-classics-montreal-biosphere-buckminster-fuller

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070123031406/http://biosphere.ec.gc.ca/History-WS7DD2D209-1_En.htm