Beijing is set to host the 2022 Winter Olympics, the first time the city will host the Olympics since the 2008 Summer Games. Amidst the extraordinary circumstances of COVID-19 and the subsequent postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, both the social and economic burden of hosting the Olympics is brought to attention. The building of Olympic stadiums transforms areas into massive construction sites — and can often result in negative consequences such as the displacement of local communities. The pressures and requirements of venues for the Olympics often produce grandiose venues built for a very specific purpose under a fixed timeline. This can create a unique concern for Olympic host cities related to the legacy or utilization of Olympic venues after the Games, in which some Olympic stadiums remain unused, and at times abandoned without function. Such cases are well documented in cities such as Athens and Rio, and certain stadiums in Beijing, China.2 In her essay, “Adaptable design in Olympic Construction,” author Laura Brown delves into how the pressure of international expectations can result in the creation of venues that are then,” retrospectively repurposed” after the games — rather than the post-Games use of the buildings remaining at the 3 forefronts of design throughout the process.”

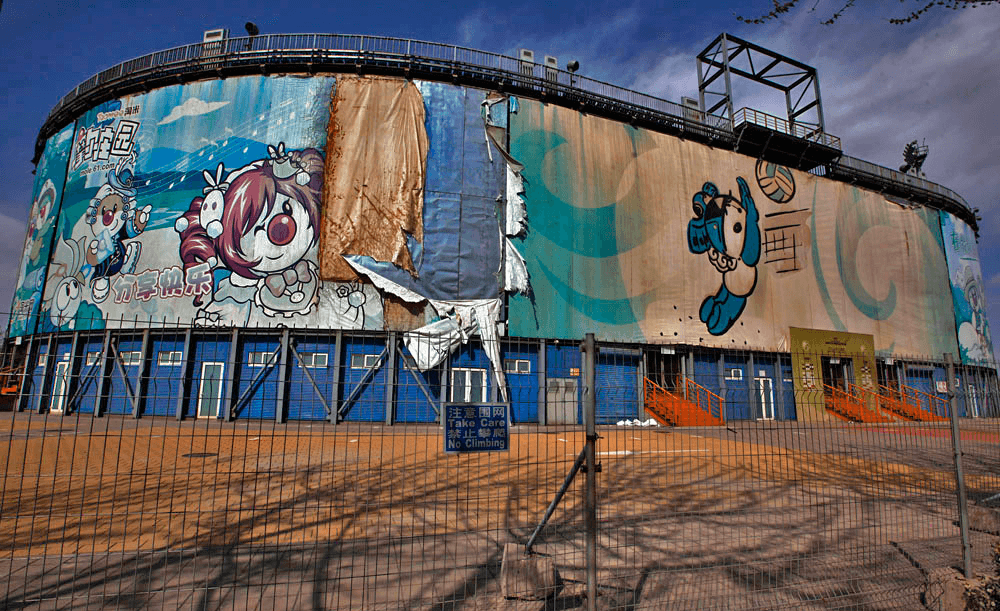

I became interested in the photo of the abandoned “Beach Volleyball Ground” in

Chaoyang park, Chaoyang district built for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, in This Atlantic article titled “Chinese Architecture, Old and New” I was drawn to this topic because the neglected venue demonstrates the ongoing challenges architects face in the building of Olympic stadiums, and the significance of contemporary abandoned buildings.

In the book Time in Architecture, Dr. Jill Stoner describes the recent development, or “new genre” of “the exploration of abandoned buildings and towns [which] has become a new kind of adventure travel.”6 Perhaps we can characterize this genre with an augmented fascination to document neglected buildings or structures that were once impressive, but now act as a marker of failure. Whether it was the failure to deliver its purpose or legacy, pictures such as the abandoned Chaoyang Park Beach Volleyball Ground suggests a failure in long-term construction and use.

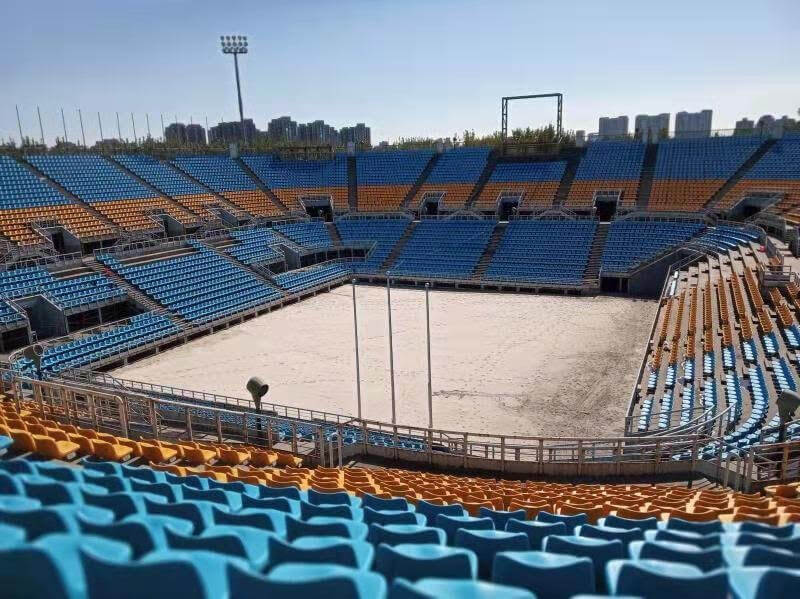

There are limited sources on the current usage of the Olympic Beach Volleyball Court, and it is easier to find photos of the venue in its abandoned state such as this article, titled “Serving to Ghosts at Beijing’s Abandoned Olympic Beach Volleyball court.”7 This set of photos shows a completely neglected building with endless rows of empty seats which is how the Beach Volleyball Court is largely remembered or documented now.

In taking a closer look at the Chaoyang beach volleyball ground, Xiaowei Yu’s Thesis “Question of Legacy,” was one of the main and most detailed sources on Beijing’s Olympic constructions. Yu’s research details how The Chaoyang beach volleyball ground was originally built as a ‘temporary’ Olympic venue– and according to the ‘candidature file of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games bid,” the volleyball ground was set to be dismantled after the games.9

Xiaomei suggests that one reason behind its current abandoned state is due to the lack of “criteria and specifications for ‘temporary sports venues,’ the design of the venue became one based on the criteria for permanent buildings – leading to a permanent sports facility.” This points to the main challenge architects face — being able to balance the requirements of a functional sports facility with the question of a unique and sustainable design.

In 2009, a beach-theme park and a swimming pool were established beside the venue.12 The renovated park in Chaoyang included three separate areas for swimming, beach recreation, and beach volleyball. 13 The facilities and stadium were utilized in the June 2011 FIVB Beach Volleyball Swatch World Tour, as well as the ‘2011 Beijing Grand Slam.”

The Chaoyang Beach Volleyball ground then was not completely neglected after the Olympic Games, rather, there were considerable efforts to incorporate it into new green spaces and future sporting events. However, as Yu writes in his thesis, there is a “scarcity of literature sources […] regarding the post-Games utilization of Beijing Olympic Venues,” and lists this as one of the main limitations for his research.15

It remains an area that has not been analyzed or examined in detail, and as such, difficult to outline the development and planning of the venue. The question of a venue or stadium’s legacy, as well as the legacy of previous Olympic games, is interesting to keep in mind, as we approach the 2022 Winter Olympics.

References:

6 Jill Stoner, “The 9 Lives of Buildings,” in Architecture Timed: Designing with Time in Mind, ed Karen Franck,

7 (Chicester: John Wiley and Sons, 2016), 19.

Burbex Brin,“ Serving to Ghosts at Beijing’s Abandoned Olympic Beach Volleyball Court,” the Beijinger, last modified October 29, 2018,

https://www.thebeijinger.com/blog/2018/10/29/serving-ghosts-beijings-abandoned-olympic-beach-volleyball-court

8 Burbex Brin,“ Serving to Ghosts at Beijing’s Abandoned Olympic Beach Volleyball Court.”

9 Xiaowei Yu, “The Question of Legacy and the 2008 Olympic Games: An Exploration of Post-Games Utilization of Olympic Sport Venues in Beijing,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Western Ontario, 2012), 98.

11 Xiaowei Yu, “The Question of Legacy and the 2008 Olympic Games: An Exploration of Post-Games Utilization of Olympic Sport Venues in Beijing,”

12 China.org.cn, “Chaoyang Park Beach Volleyball Venue,” modified from Xinhua News Agency April 4, 2007,

http://www.china.org.cn/olympic/2007-04/04/content_1206041.ht12